By: Sonora Slater for The Dirt

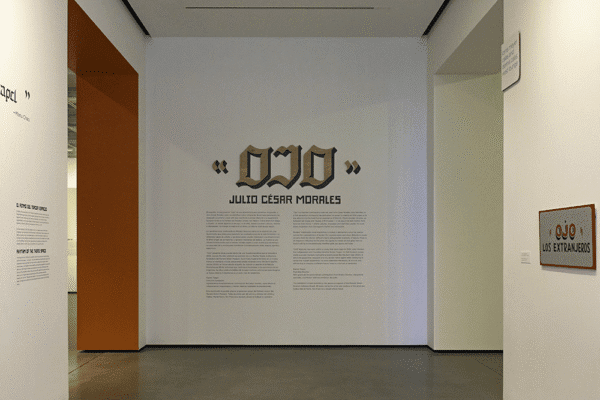

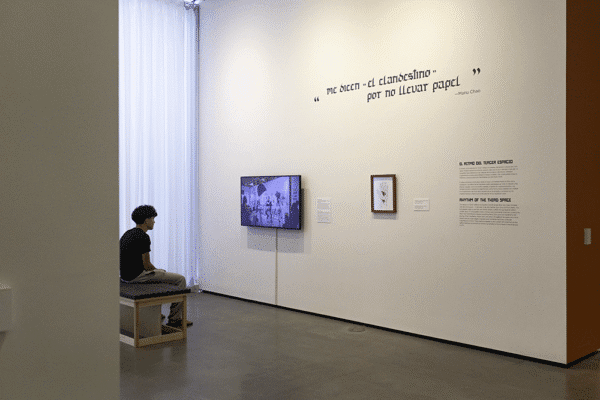

When you walk through the doorway at the Manetti Shrem Museum of Art into’ “OJO” Julio César Morales, you cross a threshold clearly delineated by a bright orange border. That’s intentional — and so is every other detail of the art and the exhibition design within, down to the screws used to hold together handmade benches built as gallery seating.

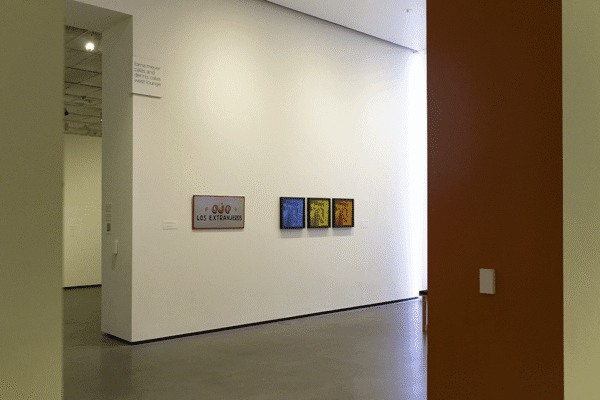

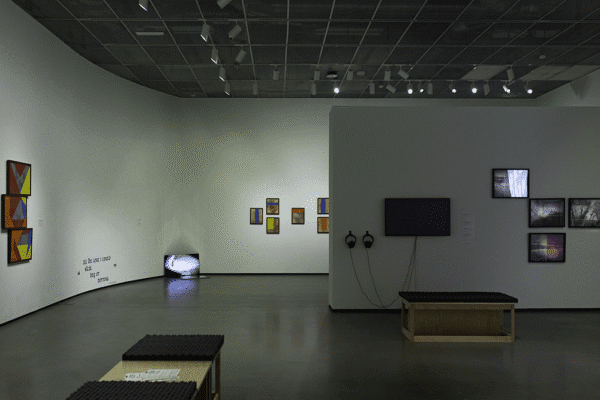

The exhibit explores real-life perspectives, stories and complexities surrounding the U.S.-Mexico border, some of which is drawn from Morales’ own experiences growing up in Tijuana and Southern California. The display includes more than 50 works across a variety of mediums, from acrylics, to watercolor, to film photography and collage.

And before any members of the public stepped foot inside the exhibit, Exhibition Assistant and UC Davis Alumni Hector Valdivia worked closely with Morales to craft an entire visitor experience for this collection of artwork.

“I felt really connected to Julio’s work and to his experiences,” Valdivia told The Dirt during a walkthrough of the exhibit. “So I really dove in and threw myself into the project.”

Valdivia’s work marks the first time that one of the Shrem’s own staff members has been the lead on exhibition design, in collaboration, of course, with the artist. And he certainly rose to the occasion, pouring thought into each immersive detail.

“Every detail was part of a larger conversation we had,” Valdivia said. “It’s things small enough that you might not notice each one, but when the subtleties accumulate, it creates this great experience.”

For some museum exhibits, crafting the visitor experience might simply mean where to place each piece of art on the wall. For “OJO,” it got a little more nuanced.

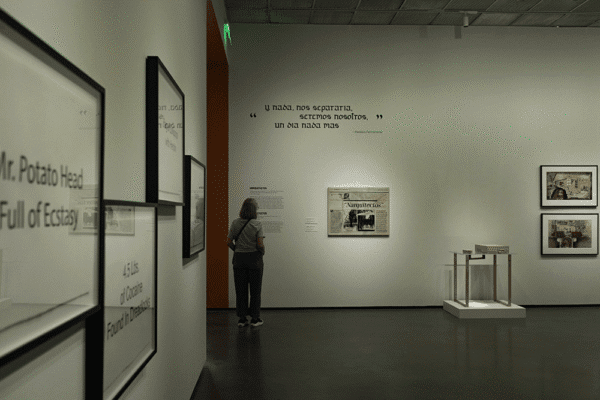

The orange band of paint around the entrance to the exhibit is a physical boundary that immediately connects visitors with the journey many migrants take across the U.S. Mexico border. Throughout the exhibit, intentionally imperfect rótulo, a traditional Mexican and Latin American form of hand-painted sign-making, was used to label walls with the names of each piece in block letters. Raw wood, along with other rough construction materials, was incorporated into furniture, signage, and so on, at the request of the artist.

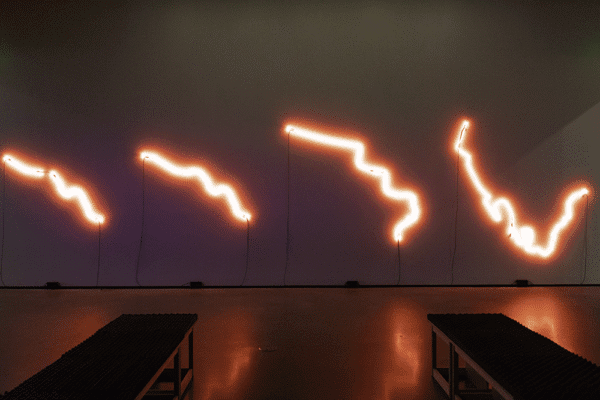

“We could’ve bought furniture,” Valdivia said. “But we decided to build it in-house instead. We used rough, inconsistent, blemished materials, and no material that was too precious. It’s meant to be used. It’s celebrating and highlighting unseen manual labor.”

Inviting engagement

“Art can be intimidating, especially to people who aren’t familiar with it,” Valdivia said. “So we think a lot about how we can design these things to create all sorts of entry points.”

The ‘OJO’ exhibit is dynamic, including a variety of those entry points. A documentarian-style ‘Meet the Artist’ video plays in the first room of the gallery, as well as other audiovisual elements throughout the exhibit, visitors are encouraged to scan a code with a playlist handcrafted by Morales to pair with the exhibit (lyrics from some of these songs are even painted onto the walls throughout the galleries, paired with certain works), and a reflection space where visitors can are encouraged to reckon with themes of the work.

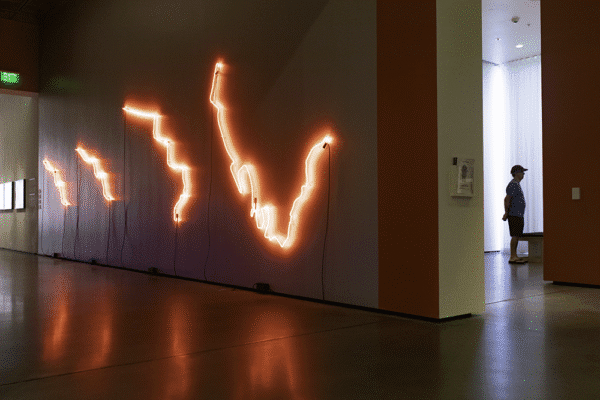

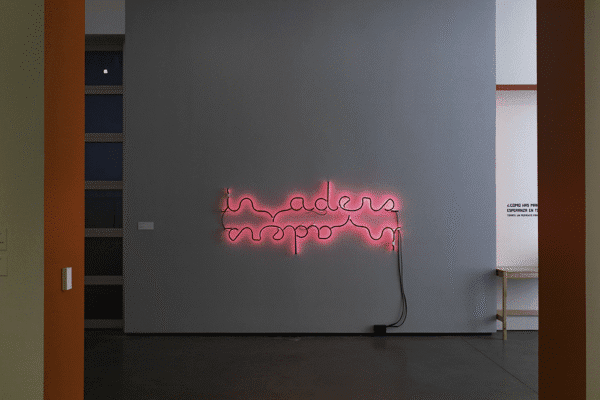

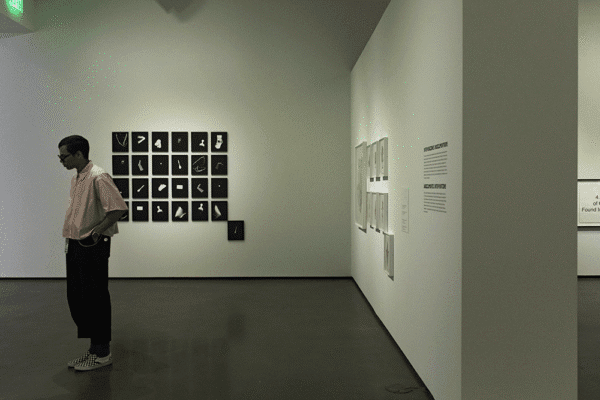

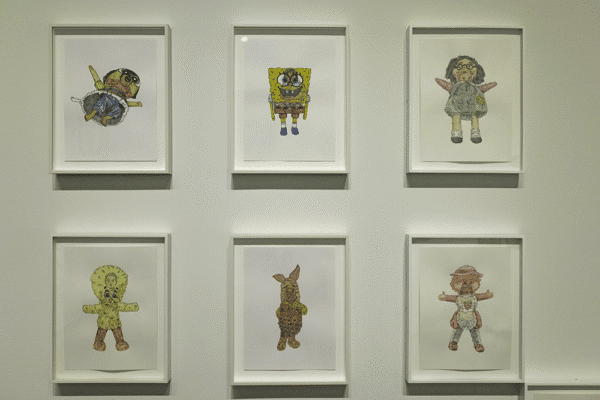

Morales’ work is naturally engaging through its multimedium diversity. From neon signs, to video, large text pieces, and even documentation of personal belongings found along migrant routes,dropped and lost throughout their journey. Another series of reimagined X-ray scans of migrant children caught hiding in huge piñata versions of Spongebob, Strawberry Shortcake, Power Puff Girls, and other American cartoon heroes in an attempt to make it across the border undetected.

With bright colors and soft brush strokes, Morales used watercolor for the portraits to soften the harsh story he is telling with the series — one of many ways in which complexity and contradiction emerge as another theme of the exhibit.

Ni de aquí ni de allá. Neither from here nor from there. This phrase sums up Morales’ own complex family history, having lived on both sides of the border, but it also acts abstractly as a representation of the many contrasting perspectives on and aspects of the border.

“In my family, [there] are relatives that are smugglers, police officers, judges, workers in the Mexican government and municipal in Tijuana as well as professors and wine makers,” Morales explained. “So all these make for a diverse experience.”

Tomorrow is for those who can see it coming

The work in ‘OJO’ plays with time. It spans more than 15 years of Morales’ life, and focuses on various points on the past, the current moment and the potential future. One of the lyrics Morales chose for the exhibit, a line from a David Bowie song, touches on this, saying, “Tomorrow is for those who can see it coming.” But possibly the clearest example of this theme in the exhibit is in a series of neon line drawings called, ‘Las lineas.’

The four pieces depict the U.S. Mexico border at various points in time, from the pre-colonial era in 1640, through to 2028, by which point Morales predicts California and New Mexico seceding from the United States.

Planning exhibits often begins years in advance, Valdivina noted. He believes it was “serendipitous” that Morales’ work is on display at the Museum during a time when immigration is such a divisive social issue.

“What comes to mind right now for me is a quote from Mark Twain, ‘History does not repeat itself, but it does rhyme,’” Morales said of the exhibit’s timing. “This brings to mind what is going on with the current cultural climate. I would like people to […] remember the history of the United States and that we are made from immigrants.”

“OJO,” the name of the exhibit, is not directly translatable to English. Literally, it translates to ‘eye,’ but it can also mean ‘Watch out!’ or ‘Be careful!’ Valdivia suggested yet another way of interpreting the word.

“It’s a call for attention,” he said. “It’s saying, ‘Look!’”